A recent UNLV study investigated the link between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease in lab rats. The test and control group were both subjected to a maze test and found working memory and spatial awareness in the rats had behavioral impairment with those tasks.

“There are a number of risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s disease,” Jefferson Kinney, UNLV assistant professor, said. “Advanced age is one, obesity is one but another one is diabetes.”

In achieving the animal testing phase, researchers enriched the blood of one set of lab rats to reach a high sugar state, mimicing the effects of diabetes as the test subjects. The other set of rats are control subjects where nothing is done to them, according to the study.

The rats were put to the test by having them go through a T-shaped maze where they will run down a path and decide to go either left or right. To get a reward, the rats must run in a figure-eight pattern. In order to achieve the figure-eight pattern, the rats have to start in either left or right direction and then go back to the opposite direction to receive the reward.

This maze specifically tests for working memory and spatial awareness, two areas that patients with Alzheimer’s disease have trouble with. Working memory gives the brain the ability to differentiate relevant information from background information and maintain the memory. Spatial awareness is knowing where the body is in space in relation to objects near and far or other people, according to the Wales University Health Board.

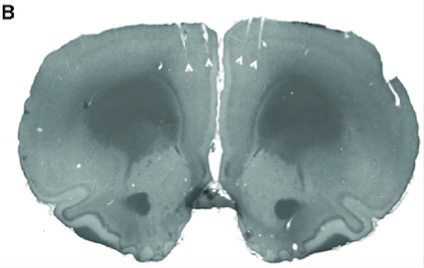

The experiments found that rats induced with sugar-enriched blood had trouble with these tasks when they were held for longer intervals before re-doing their test, when compared to the control group. Before each run, the researchers would hold onto the rats for differing intervals of time to test their memory. The analysis of the animals’ brain activity later confirmed this difference.

“For the animals to actually perform well, they need to desynchronize, which is very counterintuitive,” James Hyman, UNLV associate professor, said. “Usually we’re thinking these parts of the brain need to work together. Here they’re working together so intently, that they’re not able to function individually, so they kind of need to separate for a bit is what we found, and then animals are able to do the harder problems.”

Hyman described this state as hypersynchrony, and it is a state of the brain that is also seen in patients of Alzheimer’s disease. This study also found an elevated amount of a protein called tau, in the brains of the sugar-enriched blood rats.

Tau by itself is not harmful. However, too much of the protein causes it to clump together. These clumps of tau are one of the core pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease.

Additionally, prolonged states of inflammation in the brain are another pathology of Alzheimer’s, and also a symptom of diabetes, according to Hyman. The study that the brains of the sugar-enriched blood rats also showed inflammation.

The research team is currently conducting experiments on mice, looking into variables with diabetes outside of the specific untreated sugar-enriched blood model used on the rats in this experiment. They are also looking specifically into the possible connection between the brain inflammation present with diabetes and the inflammation also present in Alzheimer’s disease.

“We can now do two things,” Kinney said. “The first is we can try and piece together by manipulating very specific pathways, we can start to see what part of hyperglycemia is resulting in the pathological features and the changes in network function.”

Kinney believes that science is all about finding a good measure that is sensitive and would allow a researcher to then try and look at what the mechanism is.

“We have multiple measures that show Alzheimer’s related changes that now we can start manipulating specific pathways where we can start to alleviate Alzheimer’s-like pathology,” Kinney said. “So, we get to study what’s causing it, but we also have a pathway to try to figure out whether or not we can stop it.”