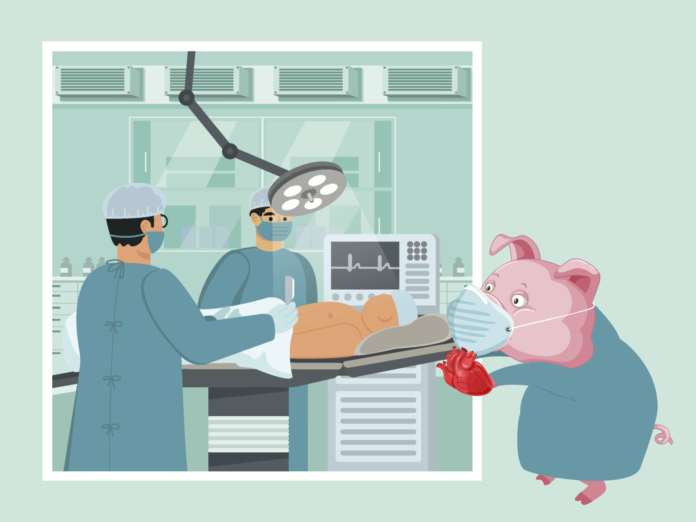

In a last effort to save David Bennett’s life, through a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved surgery, a pig heart was transplanted into a 57-year-old man to avoid death.

The University of Maryland Medical Center just performed a successful heart transplant into a man who was dying of heart disease and a shortage of human organs, according to Nature, the science journal. Bennett was placed on cardiac support for nearly two months before signing up to be the recipient of the pig heart.

Research in xenotransplantation, where animal organs are transplanted into a human, dates back to the 17th century. With the most notable strides in the 19th century where Keith Reemtsma, a surgeon, transplanted chimpanzees’ kidneys into humans in 1964. The finding of this research was that the kidneys of a chimpanzee are not large enough, as many died between week four and eight due to rejection.

The dean of the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV, Marc J. Kahn explains why the body begins to reject what might be a perfectly good organ, but the immune system does not recognize that.

“Our immune system recognizes parts of cells and tissues that are foreign,” Kahn said. “And that’s what leads to tissue rejection. The pig was modified so that its cells didn’t express those foreign antigens they’re called, so that it wouldn’t be recognized by the human immune system. And the immune system would be tolerant to the pig organ”

Before Bennett’s surgery, at the New York University Langone Health performed the second successful xenotransplantation. On Nov. 22, surgeons transplanted the kidneys of a genetically modified pig into a human patient that was legally dead, with no brain function, according to Nature. This pig comes from the same line of genetically modified pigs that Bennett received his heart transplant.

Many xenotransplantations that involve kidneys and hearts have been unsuccessful until now, according to the United States Department of Health and Human Service. After Reemtsma’s kidney xenotransplantation, James Hardy, who performed the first lung allotransplant, human-to-human transplant, was impressed by the findings. Hardy in 1964, decided he would try transplanting a chimpanzee’s heart into a human who would not have been accepted for a heart transplant today. The chimpanzee’s heart proved to not be large enough to handle a human body and the recipient died hours later.

The most well known cardiac xenotransplantation was in 1983 by Leonard Bailey, a surgeon. Bailey transplanted a baboon’s heart into an infant girl, named Baby Faye. The procedure was successful and Faye lived for an extra 20 days before her body’s immune system rejected the organ. Another factor that contributed to rejection of the organ was the conflict of blood type. Faye was of O blood type and baboons were not found to have this blood type, leading to a quicker rejection.

“The technology behind the pig heart transplant is a genetically modified pig.” said Kahn. “It’s organ’s wouldn’t be rejected by the human immune system. They transplanted a pig heart, which is a little bit smaller, but roughly the size of the human heart. And again the innovation is such that the heart was not rejected by the immune system. So this potentially opens the doors for a whole new source of organs for transplant.”

Bennett is the first person to receive a heart transplant from a genetically modified pig, but is not his first heart operation. In 2013, he received a pig’s heart valve that would not count as a xenotransplantation.

He continued to have complications with his cardiac system, where he was placed on cardiac support, but would not qualify for a mechanical heart pump due to irregularities in his heart beat. Bennett would not even be accepted for human transplant after a revision of his medical history, where he would not refill his medication and not follow medical instructions.

“It is ground breaking, we’ve been talking about this for several years now, but this is the first demonstration that it actually works,” Kahn said.

Research on genetically modified pigs and their hearts has been studied with baboons. Surgeons have been transplanting the pigs hearts and putting them into baboons. Bennett’s surgery is the stepping stone to the next phase into clinical trials to combat the organ donor shortage.

“For kidneys, we have two organs [in our bodies],” Kahn said. “So there are living donors that donate a kidney, either to a loved one or otherwise. But for things like hearts, we only have one heart, so the only way we are able to harvest hearts for transplant are cadaveric organs, so somebody who typically dies tragically in an accident and who agrees that their organs can be harvested for transplant.”

Kahn points out that when drivers sign up to get their driver’s license in Nevada, they are asked if they would be willing to be an organ donor. Some states actually have modified that procedure that applicants actually don’t have to opt in, they are immediately in. Everyone is assumed to be an organ donor, unless they opt out.

With time for more clinical trials, the medical field is eager to find a solution to the donor organ shortage. Revivicor, the company that had the genetically modified pig, wished to not disclose the cost of the pig, but it was a pretty penny. The company is in Blacksburg, Virginia, which has a facility that met the FDA’s approval for clinical trials, but is building a larger building that could supply hundreds of organs a year, according to Nature. But when will the world be ready for xenotransplantation?

“I think eventually, we’re not there yet. Right? We have an [example] of one.” Kahn said. “This is the first one that we’ve done, but this is going to be a very fruitful area of research and technology, to again, increase the number of organs available for transplant.”

As the technology advances, there is an up cry in a clarification on ethics. Jeremy Chapman, a retired transplant surgeon at the University of Sydney in Australia, says to Nature that regulators and ethicists will need to define what makes a person eligible for a pig organ. Kahn was asked what this could change for the curriculum at the medical school.

“We teach ethics, there are ethical issues with firstly clinical trials,” Kahn said. “Secondly, novel therapies, so it would come up there. Are we going to specifically teach about cross species transplantation? It’s really too new to make it into the curriculum.”