The famed Japanese innovator of animation recognized globally, Hayao Miyazaki, returns to the world of cinema from his fifth retirement for his final bow before the curtains close. After he announced his canceled retirement in 2013, Hayao Miyazaki spent 10 years creating his recently featured Studio Ghibli film, “The Boy and the Heron.” Alongside Miyazaki’s beautiful hand-drawn animation was long-time famed collaborator Joe Hisaishi, who returned with another iconic orchestral score. They are known for their works together, such as “Howl’s Moving Castle,” “Spirited Away,” “Ponyo” and “Princess Mononoke.” The return of both legends to Studio Ghibli caused the bubbling anticipation for the release of the new film.

The Studio Ghibli film premiered in Japan on July 14, 2023, while fans in North America eagerly waited for the theatrical release on Dec. 8, 2023. Fans and critics alike were not disappointed after the prolonged interlude. Shortly after its debut in North America, “The Boy and the Heron” earned a satisfactory score of 97% on Rotten Tomatoes. Additionally, the film broke records by becoming the first original Japanese animation title to top the North American box office with a $12.8 million opening, according to The Harvard Crimson. “The Boy and the Heron” also earned Hayao Miyazaki his first Golden Globe nomination for best-animated motion picture alongside “Spiderman: Across the Spider-Verse,” “Elemental,” “The Super Mario Bros. Movie,” “Suzume” and “Wish.”

Like his other Studio Ghibli films, Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron” is a strikingly alluring fantasy with themes and devices familiar from previous films that naturally contain elements of the creator. However, this film may be the most personal film the animator has ever created. “How Do You Live?” is the film’s original title and is taken from the 1937 Japanese novel by Genzaburō Yoshino, a favorite childhood book of Hayao Miyazaki. As the film follows the tale of a boy growing up amid war and fear, much as Miyazaki did, the intimacy between the creator and the audience is felt through the clear elements of autobiographical resonance.

The film takes place in early 1940s wartime Japan and centers around 12-year-old Mahito (Soma Santoki/Luca Padovan). Opening with a stark sequence of war and violence, Mahito races through a fiery, engulfed Tokyo as he desperately searches for his mother. This grim scene is one of the many autobiographical elements of “The Boy and the Heron,” citing Miyazaki’s first memories from his childhood. “My first memories are of bombed-out cities,” Miyazaki writes in his interview compilation and memoir, “Starting Point.” Subsequent to the disorienting and visually dark chase is a scene of Mahito’s mother being consumed in a hospital fire.

Mahito’s father, Shoichi Maki (Takuya Kimura/Christian Bale), is the boss of a factory that manufactures Japanese fighter planes and mirrors Miyazaki’s own father. Mahito’s father marries his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan), shortly after the death of Mahito’s mother. Still grieving, Mahito is forced to relocate with his new family from Tokyo to the country estate where his mother and Natsuko grew up.

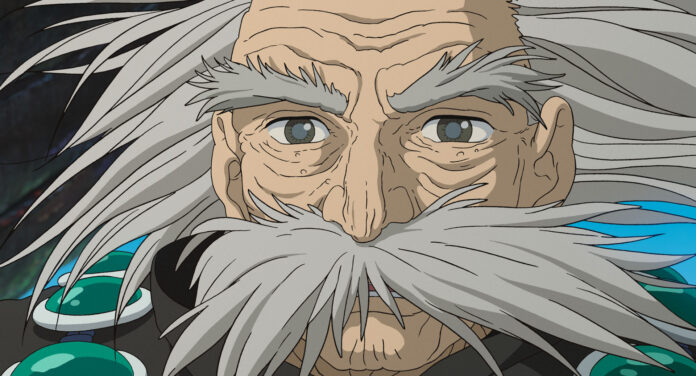

Although quietly struggling to accept his new home and reality, Mahito becomes familiar with new characters in his new life. Such as the older residents that live in the home, including Kiriko (Kô Shibasaki/Florence Pugh) and an insolent gray heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson). It seems as though the main character hits a turning point when he finds a copy of “How Do You Live?” in his mother’s childhood home. Mahito’s mother, like Miyazaki’s, gifted him the instructional coming-of-age novel. Soon after, the film slips into parallel realms as Mahito follows the heron to a forbidden tower and is drawn into a netherworld where timelines are entangled together. The movie’s pace picks up as the film enters the full depth of Miyazaki’s famed unbounded imagination. From giant man-eating parakeets to little ‘warawaras,’ the film becomes populated with enchanting characters, locations and arguably underlying exposition.

Many viewers felt as though the elusive nature of the movie overshadowed any message the creator may have been trying to convey.

Long-time fan of Studio Ghibli and marketing major at UNLV Khue Nguyen mentions how the clarity of this movie differs from other Studio Ghibli movies she has seen.

“You know, usually for the Studio Ghibli movies, the plot is kind of straightforward, but for this one, it’s kind of confusing. It has like a separate timeline throughout the story, so I was confused. I would have to watch it at least twice … just to understand it. It’s different from all the Studio Ghibli movies [I have seen].”

However, some viewers thought the film’s perplexing approach left room for an influx of reflection. English literature major at Pepperdine University Cassandra Barron says, “I was expecting it to be super whimsical and I knew that there would be different elements of magical realism in there … but I didn’t expect it to go as deep as it did; I didn’t expect so many complex messages. I feel like normally Studio Ghibli movies have one message, but I feel like this one had so many layers to it.”

Barron continues, “There were some parts of the movie I didn’t fully understand. It’s a movie you can watch more than once. It’s like I want to watch it again and see what I can get next time. That’s what I like so much about it. There are so many elements that go into it so you can go back and learn more and see more.”

“The Boy and the Heron” containing the familiar childlike essence seen in his other movies doesn’t shy away from showing the creator’s well-known juxtaposing pessimism on life. The film is as mesmerizing and densely detailed as Miyazaki’s other works, but this film is much darker and more horror-influenced than any of his other pieces. Like his other movies, the creator can’t help but insert a piece of himself into his art form. But this time, the 87-year-old offers a hand to the audience to see his most inner reflections if they’re willing to find it in the chaotic but beautiful spirit of the film.

As the movie moves to the final act, the blurry connotation of the film inches closer to clarity as all the pieces rapidly start to fall into place.

After watching Mahito’s and the young fire maiden Himi’s (Aimyon/Karen Fukuhara) instant familiarity with each other grow throughout the film, it is evident to the audience that Kimi is Mahito’s mother as her younger self. Kimi and Mahito’s relationship represents Miyazaki’s close relationship with his mother who was hospitalized most of his life and eventually died from tuberculosis.

Towards the end, Mahito is eventually confronted by his elderly great uncle, the creator of the world, to rebuild the tower — as his successor. If the metaphor wasn’t clear enough, the aging creator seeking a successor for his soon-to-be crumbling world is a stand-in for Miyazaki himself. This connects to Miyazaki’s struggle to find a successor to lead his legacy at Studio Ghibli and represents Miyazaki’s most personal perturbation. Will Miyazaki find someone who will stack the building blocks of the vast and beautiful world he created? Or will the world, known as his imagination, come crumbling down? Will everyone forget the world he created and move on after he is gone? “The Boy and the Heron,” Miyazaki’s last film, is not just a testament to his beloved and magically endearing films but ultimately his life. The creator has been reflecting on his role in life, his artform and the world he will eventually leave behind. The film, following the story of Mahito and how he lived, proposes Miyazaki’s grand question for the audience: How do you live? How will you? Will you grieve, grow and continue on?