Prestige means everything in the art world. What museum does an artist display their work in? Who purchases the artwork? Who curates the artwork? It meant everything, until artist Keith Haring upended elitism and rejected prestige in art.

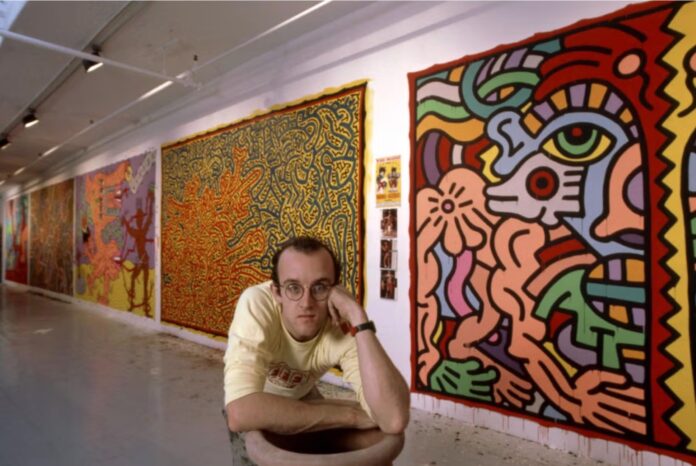

With Keith Haring, people don’t normally recognize specific works of art, like how people recognize that “The Creation of Adam” was painted by Michelangelo. Rather, they notice his signature, and timeless style. Haring’s style consists of thick outlines of people in abstract poses, and those outlines are filled in with vibrant colors. His art often conveyed political messages. For example, “Free South Africa” advocated for the end of apartheid, where White minority groups held power over the majority Black native group. “Free South America” was printed on posters, shirts and postcards, leading to the release of Nelson Mandela. Hating did a mural in Harlem, New York called “Crack is Wack,” raising awareness for drug addiction. What makes Haring stand out is his unique and rare ability to capture his personality in his art. This uniqueness is personified in his life too, as he was always taking unconventional paths in life that other artists were too afraid to.

According to a biography on his foundation’s website, Haring was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, learning to draw at an early age. As a young artist, he learned to draw cartoons from his father, taking inspiration from children’s books and cartoons. After graduating from high school, Haring went to the Pittsburgh College for Illustration. While he was there, he found some of the rules stifling and restrictive. For example, a student had to get permission from the administration to hang up art on the wall, so he rebelled by hanging up some of his art on the walls without getting permission as an impromptu exhibition. Soon after, he dropped out of college. After dropping out, he hitchhiked his way to New York and immediately noticed empty advertising boards in the New York Subway. He would draw those iconic figures using chalk. This is where his art took off, with everyday commuters recognizing his signature style, and there soon became a rush to take down his art and sell it for themselves. He was fined and arrested several times for defacing public property. In an interview with The Guardian, he shared, “The public has a right to art. The public is being ignored by most contemporary artists. Art is for everybody.” He believed that art should be accessible to as many people as possible, opening up a pop-up shop to sell his art at a low cost. He found a way to connect his art to a broader audience, upsetting museum curators because the accessibility and affordability of his art questioned why their careers existed. At the same time his work was taking off, Haring lost several friends to AIDS and sought to create art that promoted the concept of safe sex.

NBC published a reflection on the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s, writing that it was not taken seriously because it became linked with homosexuality. According to the CDC, by 1991, the disease had killed over 100,000 people. In an interview with Rolling Stone Magazine in 1989, Haring said, “AIDS has made it even harder for people to accept because homosexuality has been made to be synonymous with death. It’s a justifiable fright with people that are just totally uninformed and therefore ignorant. Now it means that you’re a potential harborer of death. That’s why it is so important for people to know what AIDS is and what it isn’t.” Haring adds, “In the United States, people are shy to talk about safe-sex… A lot of what we see here is more tame because people’s preconceived notions of what they think people can handle. In fact, when people are treated as if they have some intelligence and are given explicit information, they appreciate it.” His piece, “Rebel with Many Causes,” called out the American public’s avoidance of speaking about safe sex. It questions the “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” mindset on the AIDS pandemic.

Haring risked his reputation within the art community and financial stability to spread awareness of AIDS. He did not take the traditional path of artists getting famous, having their art in expensive museums and catering to art curators. He focused on making his art available to the public and that didn’t derail or damage his legacy, rather, cementing his place in the annals of art history.